THE HOLTZLAU‑HOLTZCLAW FAMILY

The origin of the family is from the very ancient parish of Holtzklau, first mentioned in 1089, with a parish church dating back to the 13th century in the central village of Oberholzklau, and a number of other villages in the parish, including Niederholzklau. There is a brook called the Klav (an ancient name for a gully or ravine) which runs through the parish, so that the name means "the woods of the Klav." The brook later changes its name to the Ferndorf, runs through Klafeld (the "field of the Klav"), and joins the river Sieg at Weidenau. Holzklau has always been an almost exclusively agricultural parish. The case is different wiidenau ef Weidenau, when our ancestors liv\\\

ed there, the township (Gemeinde) contained seven iron‑works settlements as well, Hardt, Muenkershuetten, Muesenershutten, Meinhardt, Schneppenkauten, Fiskenhuetten and Buschgotthardshuetten. Through marriages in the third and fourth generations of the pedigree given above, the Holzklaus of Weidenau became connected with the ironworks people there, particularly in the family of Johannes Holzklau of Weidenau, Jacob Holtzclaw's grandfather.

First Generation

Hans Henrich Hotzklau Born circa 1658 Married: to Gertrud (Patt) Solbach.

|

i |

Hans Jacob Holtzclaw | |

ii |

Johannnes Hotzklau |

Second Generation

Hans Jacob Holtzclaw Born:1683 - Nassau-Siegen Father:Hans Henrich Hotzklau Mother:Gertrud (Patt) Solbach Married: to Anna Margreth Otterbach

Children:

|

i |

Johannas Holtzclaw | |

ii |

Johann Henrick Holtzclaw | |

iii |

Ann Elizabeth Holtzclaw | |

iv |

Katherine Holtzclaw | |

v |

Harman Holtzclaw | |

vi |

Elizabeth Holtzclaw | |

vii |

Alice Katerine Holtzclaw |

|

viii |

Jacob Holtzclaw | |

ix |

Eve Holtclaw | |

x |

Henry Holtzclaw |

Third Generation

Johannas Holtzclaw (aka John) Born:1709 - Nassau-Siegen Died:1752 - Prince William Co. VA Father: Hans Jacob Holtzclaw Mother: Anna Margreth Otterbach. Married: ABT 1730 to Catherine Thomas Russell

Children:

|

i |

Henry Holtzclaw | |

ii |

Joseph Holtzclaw | |

iii |

Elizabeth Ann Holtzclaw | |

iv |

Mary Holtzclaw | |

v |

Benjamin Holtzclaw | |

vi |

Josiah Holtzclaw | |

vii |

Catherine Holtzclaw,

4th Generation Holtzclaw, married Joseph Martin and had Nimrod Martin who married Fanny Hopwood and had Frances Martin who married George Washington Austin and had Mahulda Austin who married William Buchanan and had Frances Buchanan who married John Wesley Apple and had George Thomas Apple who married Mariah Bell and had Jennie Apple who married Erastus Montague and had Vivian Lucile Montague who married William Ratcliff and had Barbara Ratcliff my mom. |

|

Nimrod Martin |

Joseph Martin |

John Joseph Martin |

| |

| |

Maria Kathrina Otterbach |

| |

| |

Catherine Holtzclaw |

Johannas Holtzclaw |

Hans Jacob Holtzclaw | |

Anna Margreth Otterbach | |

Catherine Thomas Russell |

| |

| |

Frances Martin | |

Fanny Hopwood |

Christopher A. Hopwood |

Moses Hopwood |

Richard Hopwood | |

Mary (Unknown) | |

Elizabeth Pridham |

Christopher Pridham | |

Mary Lewis | |

Martha Combs |

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

|

THE 1714 GERMANNA COLONISTS IN VIRGINIA THE 1714 GERMANNA COLONISTS IN VIRGINIA

Until 1815 Nassau-Siegen, now a part of Westphalia, West Germany, belonged to the House of Nassau from Holland. The Counts of Nassau had large possessions in Germany from very early times, perhaps as early as the age of Charlemagne. Siegen, the hub city of this province, is situated on the river Sieg, which flows into the Rhine from the east side. (B. C. Holtzclaw, ANCESTRY AND DESCENDANTS OF THE NASSAU-SIEGEN IMMIGRANTS TO VIRGINIA 1714-1750, Germanna Record No. Five, (Culpepper, VA: The Memorial Foundation of the Germanna Colonies in Virginia, Inc.,1964)) Siegen is 49 miles east and slightly south from Cologne; 45 miles east and slightly northeast from Bonn; and about 40 miles northeast from Coblenz; all these distances measured in air miles.

Nassau-Siegen has always been rich in iron ore, frequently very near the surface of the ground, and there is evidence to show that there was active production of iron in this principality from 500 B.C. to about 100 A.D., carried on by early inhabitants, who were probably Celts. For some reason this activity seems to have ceased during the early years of the Christian era, possibly because the earlier inhabitants were driven out by Germans. From the time of Charlemagne and the Franks, however, there are numerous evidences of iron production by the so-called forest smiths. That Nassau-Siegen was famous for the production of iron even in the early years is evidenced by the fact that in a Welsh poem of the 12th century, written by Geoffrey of Monmouth, the home of the legendary Wieland the Smith of the Arthurian saga, is located in the city of Siegen. There is a village in the south of Nassau-Siegen called Wilnsdorf, which in the middle ages was called "Wilandisdorf", or village of Wieland.

During the 13th century the iron industry was revolutionized in Nassau-Siegen by the discovery that water power could be used to operate the smelters and drive the hammers that worked the iron further. The Count and the nobility were at first active in founding such water-powered ironworks, but they very soon passed into the hands of worker-owners, who banded together in the Guild of Smelterers and Hammersmiths, The members of this Guild mostly lived in the country near their plants, unlike most of the members of others guilds who lived in the cities. Due to a lack of water power in the dry seasons and to a frequent scarcity of charcoal needed for heating the ore and pig iron, the ironworks could not be operated continuously throughout the year. Thus the ironworks owners nearly always farmed in addition to their work in iron. Also the farmers frequently became part owners of the iron works, through intermarriage. (B.C.Holtzclaw, ANCESTRY AND DESCENDANTS OF THE NASSAU-SIEGEN IMMIGRANTS TO VIRGINIA 1714-1750, Germanna Record No. Five,( Culpeper, VA: The Memorial Foundation of the Germanna Colonies in Virginia, Inc.,1964))

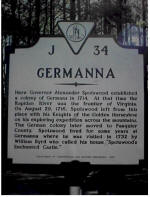

Three German groups of colonists came to Virginia during Governor Spotswood's administration and settled at or near what became Germanna. The first group consisted of 12 families numbering 42 persons, as shown by an order of the Virginia Council, passed April 28, 1714. Included in this group were some of our direct ancestors, as follows: Hans Jacob Holtzclaw. his wife Margaret ,their son John Holtzclaw , and Peter Hitt.

The settlers at Germanna in 1714 were fairly well educated people by the standards of the time. Compulsory schooling was introduced in Nassau-Siegen in the middle of the 16th century. All of this colony excepting Haeger and Holtzclaw, were raised on farms, and undoubtedly farmed land owned by them when they emigrated. Farm work was done by the women and children and at special seasons by the men who were taught mining and iron-making. The settlers at Germanna in 1714 were fairly well educated people by the standards of the time. Compulsory schooling was introduced in Nassau-Siegen in the middle of the 16th century. All of this colony excepting Haeger and Holtzclaw, were raised on farms, and undoubtedly farmed land owned by them when they emigrated. Farm work was done by the women and children and at special seasons by the men who were taught mining and iron-making.

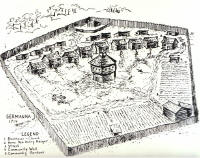

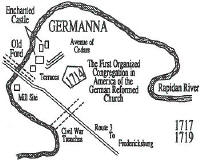

The original Germanna settlement consisted of a fort, furnished with two cannon, including ammunition, and a road cleared to the settlement. This settlement not only served as living quarters for these colonists who were to work in Governor Spotswood's ironworks , but was also regarded as security for the Virginia frontier from Indian attacks. It was located on a peninsula on the south side of the Rapidan River, which is the southern (more properly the western) branch of the Rappahannock, nine miles above the confluence with the northern branch and 13 miles above the site of Governor Spotswood's iron works.

The twelve families of the 1714 colony finished their work for Governor Spotswood in December 1718. Apparently they felt that they were being imposed upon by the Governor and wished to take advantage of the opportunities for bettering their lot in their new country. Therefore, sometime in 1718 John Fishback, John Hoffman, and Jacob Holtzclaw, the three members of the colony who had been naturalized, made an entry of approximately 1800 acres of land in the Northern Neck of Virginia. There a settlement was eventually founded which became known as Germantown. The colonists probably moved to their new location sometime in 1719; however, the actual patent for Germantown was not made until August 22, 1724, due to the death of Lady Fairfax. Germantown, which no longer exists , was located in what is now Fauquier County, Virginia.

The Memorial Foundation of the Germanna Colonies, Inc., Box 693, Culpeper, Va. 22701, established in 1956, purchased the original site of Germanna Colony and has instituted an archeological dig on this site. The Corporation owned 270 acres, "Siegen Forest," of the original Germanna tract. That acquisition of the property was made possible by the generosity of one of the trustees of the Foundation. Approximately 100 acres of this was given in 1969 to the State of Virginia for the erection of the Germanna Community College. By authority of the Virginia State Highway Commission, issued March 26, 1969, Virginia Route #3 from Culpeper to Fredericksburg has been designated GERMANNA HIGHWAY. This highway borders "Siegen Forest" and traverses the area where the first colony of 1714 was settled by Governor Spotswood.

The Foundation has published 13 different Germanna Records containing a wealth of information on the colonists, including much on the Hitts and the Holtzclaws. All of the information included in this genealogy on Germanna Colony and the ancestry of the Hitts and the Holtzclaws which follows was obtained from the following Germanna Records:

Holtzclaw, B.C. Peter Hitt, John Joseph Martin, and Tillman Weaver of the 1714 Colony and heir descendants, Germanna Record No.1

Holtzclaw, B.C. and Hackley, W.B. Germantown Revived., Germanna Record No. 2.

Holtzclaw, B.C. Ancestry and Descendants of the Nassau-Siegen immigrants of Virginia, 1714-1750. Germanna Record No. 5.

Holtzclaw, B.C. and Wayland, John W. Germanna, Outpost of Adventure. Germanna Record No.7.

For more information on the Nassau- Siegen immigrants to Virginia, I highly recommend the above publications for further reading. |

The Germanna Colony of 1717

On July 12, 1717, twenty families left the area that would become Germany to go to the New World of North America. Their boat was detained in England, where the captain was imprisoned for debt. Because they were delayed while waiting for his release, their provisions ran so low that many of them perished during the crossing.

They had planned to join other German families in Pennsylvania, but storms forced the ship south, to Virginia. There the English sea captain claimed that they had not paid for their passage and refused to let them land until Gov. Alexander Spotswood paid him the amount he demanded. Spotswood, in turn, managed to get the Germans to

sign a contract that "they apparently did not fully understand." Thus members of the 1717 Germanna Colony came to America as indentured servants. Further, at the end of the customary seven-year period, Spotswood sued and compelled most of them to work an additional year, "so that they labored eight years to gain their freedom." sign a contract that "they apparently did not fully understand." Thus members of the 1717 Germanna Colony came to America as indentured servants. Further, at the end of the customary seven-year period, Spotswood sued and compelled most of them to work an additional year, "so that they labored eight years to gain their freedom."

The Germanna Colonies, John Blankenbaker

In 1713, forty-odd Germans left their homes in Nassau-Siegen expecting to mine silver in the New World. In 1717, about eighty Germans left their homes in southwest Germany expecting to go to Pennsylvania. Neither of these groups fulfilled its expectations. Instead, they became guardians of the frontier in Virginia and a vanguard in the westward expansion of English civilization on the North American continent. How did this come about, especially when the Germans themselves had no expectations of serving in these capacities? In 1713, forty-odd Germans left their homes in Nassau-Siegen expecting to mine silver in the New World. In 1717, about eighty Germans left their homes in southwest Germany expecting to go to Pennsylvania. Neither of these groups fulfilled its expectations. Instead, they became guardians of the frontier in Virginia and a vanguard in the westward expansion of English civilization on the North American continent. How did this come about, especially when the Germans themselves had no expectations of serving in these capacities?

Reviewing the events prior to the coming of the Germans, the Colony of Virginia had settled Huguenots on the James River as a buffer between the English and the Indians. Franz Michel in Switzerland wondered if the Swiss might not do the same thing in Virginia and establish colonies where they could send people, including Anabaptists whom they did not desire in Switzerland. Michel went to Virginia where he explored the possibilities. He liked what he saw and heard. Back in Bern, he reported to his partners who unsuccessfully attempted to obtain a concession for a Swiss colony from Queen Anne of England. Michel, meanwhile, returned to America for several years of further exploration. The Swiss entrepreneurs were approaching this venture as an opportunity to earn money. There were no altruistic motives.

The reports of Michel inflamed Christoph von Graffenried of Bern who was looking for a way to restore his status and financial health. Graffenried was especially intrigued by Michels report that he had found silver mines. Graffenried joined Michels company (Georg Ritter and Company) and provided the necessary spark to ignite action. Though colonization was the primary objective, silver mining was promoted to equal importance.

By a coincidence, this was the year, 1709, when so many Germans were in London expecting that Queen Anne would provide transportation for the emigrants who wanted to go to the English colonies.

The proprietors of North Carolina had obtained permission to send several hundred of the thousands of Germans in London to their colony. These proprietors agreed to provided transportation for an initial group of Swiss if Graffenried would be responsible for the Germans they were sending over. Believing he could pursue the dual objectives of colonization and silver, Graffenried agreed to lead the several hundred Germans and a smaller contingent of Swiss to North Carolina.

The silver mining was pursued by hiring Johann Justus Albrecht to purchase tools and to recruit German miners. To find the miners, Albrecht went to Siegen where there were iron mines. Graffenried thought that the North Carolina colony could be set up rather quickly and then he could devote his attention to the silver mines in Virginia. Graffenried's company had obtained the Queens approval for land in Virginia for a Swiss colony. There was no intention now to use Swiss citizens since the German miners were to live there.

In America, many misfortunes befell Graffenried. He was even lucky to escape what seemed like a certain death at the hands of the Indians. The German/Swiss colony did not prosper in these early years. Graffenried and Michel had a disagreement before Michel had shown Graffenried the location of the silver mines. Graffenried went to Virginia to see if he could find a site where he could relocate the remainder of the North Carolina colony and to see if he could find the silver mines. While he was there, he aroused the attention of Lt. Gov. Alexander Spotswood. Spotswood even invested significantly in what seemed to be a silver mine.

Graffenried had to give up in America as the colonization enterprise was bankrupt. He returned to Europe in 1713 and when he passed through London he found that Albrecht was there with forty-odd people from the Siegen area who were expecting to have the balance of their trip to the colonies financed by Graffenried. No report tells us clearly why the Germans had been motivated to go to London at this time. Graffenried, being broke, could only advise them to go home. They did not feel they could do this as they were citizens without a country. Instead, the Germans agreed to pay a part of their transportation costs and to work four years to pay for the balance. The agent for Virginia in London obligated Spotswood to pay this balance even though Spotswood himself knew nothing of the agreement.

This agent in London, Nathaniel Blakiston, was very much aware that Spotswood was interested in precious metals. He appeared on Spotswood's behalf before the Board of Trade and before Lord Orkney who was the nominal governor of Virginia. He pleaded for a resolution of the question of the royal percentage if precious metals were found. Because of Blakiston's knowledge of Spotswood's interest in these precious metals, he felt that the Germans were a good opportunity for Spotswood to obtain the labor he might be needing.

After the Germans were in Virginia, Spotswood welcomed them in the hope that they could be put to work in the projected silver mine of which he was a quarter owner. This mine was about fifteen miles beyond the western extent of English civilization so Spotswood obtained the concurrence of the Virginia Council to build a fort from the public monies for the Germans. The official explanation was that the Germans were to be the guardians of the frontier to protect the English from the Indians. They did serve in this capacity. From the land plots, one can see that the mine which seemed to have silver was only about four miles from the German settlement. As with many of Spotswood's actions, it is hard to distinguish between the public policy which he was helping to formulate and his personal interests.

Because the status of foreigners was uncertain, Spotswood was afraid that his actions might be held against him. Perhaps the naming of the fort as Germanna was a subtle appeal to Queen Anne who was favorably inclined toward Germans.

Spotswood would not allow the Germans to work in the mine until the legal title to precious metals was clarified. Therefore, the Germans did no mining for two years while instead they farmed and guarded the frontier. Eventually an attempt was made to locate silver ores but the mine was abandoned because none could be found.

Spotswood was looking for a means to insure his economic future which, as Lt. Governor, was not secure. Observing how other people in Virginia had prospered, he decided on a course of land acquisition. Most of the land in the Tidewater region had been taken up and the large tracts were all in the Piedmont to the west where there were no settlements and no roads but there were Indians. This was the best available land in the period from 1710 to 1720, especially in large tracts. This land had never been patented to private owners by the Crown and it was available relatively cheaply.

Once a private individual took up the land, he had to make improvements and to settle a certain number of people. The western lands could be raided easily by the Indians which would discourage settlers. No one wanted to be first and risk his own safety. Spotswood saw that the answer lay in obtaining a large number of people who could be settled at the same time. Their safety would be provided by their own numbers and they would provide the settlers to make a valid claim to a large tract.

The Fort Germanna Germans had done a good job in keeping the peace without creating any problems for the Virginians. Spotswood envisioned that the people he wanted and needed could be Germans.

In conversations with the captains of ships, he let them know he wanted a whole shipload of Germans. One of them, Andrew Tarbett, when he was back in England, agreed to take about eighty Germans to Pennsylvania which was where they wanted to go. Instead, he took them to Virginia on the ship Scott where he sold them as servants to Spotswood and his partners. They were settled on a tract of 40,000 acres of land (40,000 acres was the official description but the tract was closer in size to 65,000 acres) starting to the west of Germanna.

The Germans in the fort had been the western- most point of English civilization on the Atlantic seaboard. After the second group came, they were the most western point of English civilization even though, in both cases, the language and customs were German.

The first group of Germans, the miners from Nassau-Siegen, lived in the fort and worked about four years for Spotswood. During the first two years they cleared land and farmed, then for about two and half years, they worked in mining and quarrying, first at the silver mine and then with the iron ores which they had discovered. Early in 1719, they moved north to land they had purchased in the Northern Neck, just south of todays Warrenton. Before they left the employment of Spotswood, they had found and developed iron mines but they did not build an iron furnace for Spotswood. This group, which became known as the First Germanna Colony, was German Reformed by religion.

The Second Germanna Colony came from many different villages which were mostly south and east of Heidelberg with a few from outside this area. They worked seven years for Spotswood and his partners in naval stores projects and in vineyards. When they did move, they went about twenty-five miles farther west to land in the Robinson River Valley at the foot of the Blue Ridge Mountains. This again was an extremely exposed position but they chose this general region because land there was free at the time and there were few or no English settlers which gave them space for expansion. By religion they were predominantly Lutheran. In 1740, they built a church which is still being used today as a Lutheran church (it is now the oldest building in the Americas still in use as a Lutheran church).

Even before the Germans had left the vicinity of Fort Germanna, more Germans were coming. After the Germans had left the neighborhood of Fort Germanna, the newcomers moved directly to the regions where the earlier Germans were then living. These newcomers had a mixed background. Some of them had been in the English colonies for a few years and were relocating. Others came directly from Germany. Many were friends and relatives of those already here. This process continued until and after the Revolution. During the war, some of the British auxiliaries from Germany thought that farming in a German community was better than carrying a musket for the British. All of these people are called the Germanna Colonists even though the majority of them were never at Germanna and they were not members of any colony. Essentially, the common characteristic was that they lived on the east side of the Blue Ridge Mountains. The name Germanna Colonist is used because it was appropriate for the first of the Germans.

The process of finding the Germans who lived in this general region is ongoing. New names are being uncovered. Work continues also in extending their history in Europe including locations in Germany, Switzerland, and Austria.

Because many of the activities bearing on the early Germanna citizens were semi-official, there is considerable recorded history about them. Major sources of family information pertaining to the Second Colony people are their church records where there are baptismal records from 1750 to the early 1800s and communion lists from 1775 to 1812.

There is a sense of community identity among all of the Germanna people which still exists.

(Reprinted from Volume 14, number 3, (May 2002), Beyond Germanna)

Here the miners dismount in what is the westernmost point of settlement in the Virginia colony and begin to build a five-sided log fort (similar to the one at Jamestown which was built in 1607--a hundred years before).

These German immigrants establish the first settlement of the Virginia Piedmont and of what will become Orange County. It is also the oldest German settlement in the New World. This settlement is christened "Fort Germanna" both in recognition of its German settlers and to honor Queen Anne (also called "Anna"). (The Rapidan River is also named for Queen Anne: "rapid" plus "an" for "Anne"--sometimes it is written as "Rapid Ann" and "Rapidanne" in this period.) The family names of these pioneer German families prosper in America and figure prominently in the many American German ancestry genealogical societies today:

Jacob Holtzclaw, wife Margaret, sons John and Henry

John Joseph Martin, wife Maria Kathrina

John Spillman, wife Mary

Herman Fishback, wife Kathrina

John Hoffman, wife Kathrina

Joseph Coons, wife Kathrina, son John Annalis, daughter Kathrina

John Fishback, wife Agnes

Jacob Rector, wife Elizabeth, son John (ancestor of the author's wife on her mother's side)

Melchior Brumback, wife Elizabeth

Tillman Weaver, mother Ann Weaver

Peter Hitt, wife Elizabeth

Rev. John Henry Hager

John Kemper

Harman Utterback

The descendants of these German pioneers spread out across the entire country during the decades of westward expansion that follow, and five become state governors:

James Lawson Kemper (Virginia)

James Sevier Conway (Arkansas)

Elias Nelson Conway (Arkansas)

Henry Massey Rector (Arkansas)

William Meade Fishbach (Arkansas) ("Germanna History" online 2)

This fort is intended to protect the Virginia frontier and serve as a buffer against the Indians. Thanks to a description of it made in a diary by a visiting British officer, JOHN FONTAINE (who is touring the area with an interest to buying land), we know the fort has two cannons (supplied by Spotswood), nine houses (one for each of the miners with a family); small compounds around each house with outbuildings for livestock, and a central blockhouse that serves as the last point of defense if the fort is overrun. This blockhouse doubles as a church—the first congregation of the German Reformed Church in America. Their pastor is the Reverend John Henry Hager, who is born in Anzhausen in 1644 and thus is 70 years old when he arrives in Virginia in 1714. (A man of "great erudition," he dies in 1737 in Madison County, Virginia, at age 93, this according to Wayland 12.)

Here is John Fontaine's description, from his entry of 21 November 1715 of his visit to Fort Germanna:

We walked about the town, which is palisaded with stakes stuck in the ground, and laid close the one to the other, and of substance to bear out a musket-shot. There are but nine families, and they have nine houses, built all in a line; and before every house, about twenty feet distant from it, they have small sheds built for their hogs and hens, so that the hog-sties and houses make a street. The place that is paled in is a pentagon, very regularly laid out; and in the very centre there is a black-house, made with five isdes, which answer to the five sides of the great

enclosure; there are loop-holes through it, from which you may see all the sides of the inclosure. This was intended for a retreat for the people, in case they were not able to defend the palisades, if attacked by the Indians.

They make use of this block-house for divine service. They go to prayers constantly once a day, and have two sermons on Sunday. We went to hear them perform their service, which was done in their own language, which we did not understand; but they seemed to be very devout, and sang the psalms very well. (qtd. in Wayland 25) |